Walter Wallace Jr. was devoted to his family and his music. He’s not “the monster,” family says

Bucks County Courier Times / USA Today

Days after the fatal police shooting of his cousin Walter Wallace Jr., Anthony Fitzhugh said the family is “trying to get through the day, second by second,” haunted by questions that will never be answered.

“Should I have called? Should we have tried to do it ourselves?” said Fitzhugh outside the family’s home inThursday, just a few feet from where his 27-year-old cousin was shot while suffering a mental health crisis. “They’re dealing with that.”

On Wednesday, Dominique, Wallace’s wife, gave birth to his ninth child, a daughter.

“Walt was a father, son, brother, uncle, cousin, husband and a twin,” Fitzhugh said. “Now, his twin will have to celebrate her birthday alone because of this unnecessary shooting.”

His shooting death is again raising questions about how police officers respond to mental health crises. Two officers — who did not have Tasers — each fired at least seven rounds at Wallace after yelling at him to drop a knife, according to police reports. Wallace was hit in the shoulder and chest. Officers drove him to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead a short time later.

“He’s not the monster that everybody is trying to paint the picture of him being,” Fitzhugh said. “When he took his medicine, he was great. Walt loved people and he showed his love every chance he got.”

Fitzhugh said Wallace Jr. suffered from a mental illness, and when he was not on his medications, “it caused him to act out of character.”

“The few times I was around when he had (an episode), you could talk to him,” his cousin said. “You might talk to him about his music or talk about this children … get him to engage in that conversation. Stay focused on those topics, and it was easy to bring him down.”

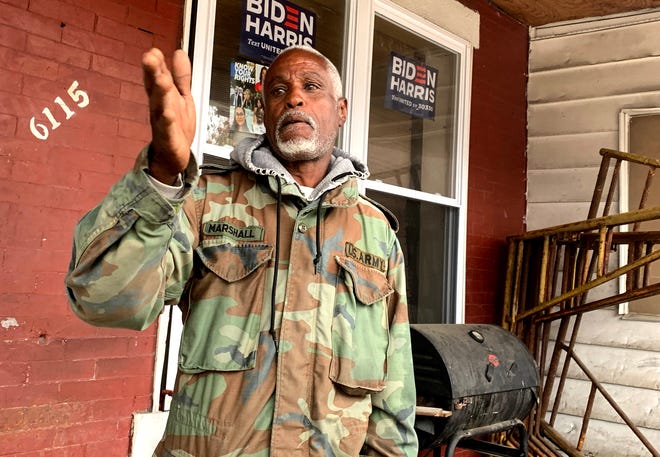

Kevin Marshall watched the events of late Monday afternoon unfold from his window across the street. He said he saw family members try to de-escalate the situation.

“I looked out the window. I saw his mom was chasing him, trying to tell police, ‘I got it. I got it.’ ”

“Everybody was saying the same thing … And they shot him.”

Video of the shooting shows Walter’s mother, Cathy Wallace, pleading with her son to walk away and screaming to police not to shoot.

A community in mourning

Along the 6100 block of Locust Street, neighbors and family members remembered Wallace for his endless energy, love for music and passion for his family and children.

Fitzhugh said Wallace was a talented rapper who aspired to “be the next Jay-Z.” Wallace, he said, threw his passion into his music and his children, who he would incorporate into his videos and songs.ADVERTISING

“He wrote about whatever he was feeling that moment,” said Fitzhugh, adding that he rapped recently about George Floyd. “He filmed a whole video about the incident. If there is a shooting up on a corner and he’s out there and around that conversation, he’ll rap about that.”

As the rain beat down on his car, Fitzhugh recalled the enthusiastic greeting he would get from Wallace. “He would always say, ‘I love you big cuz.’”

And when it came to his children, “Their wish was his command.”

“At times you would think that he was their age, the way they played football and basketball. Sometimes they would just sit and watch him rap.”

“Walt enjoyed life. He was fun and outgoing … He had big dreams of becoming a famous rap artist.”

Neighbors described the trauma the community has suffered this week.

Not far from the fatal scene, Ameer Harris described what he heard that day.

“One of the most horrible things you could hear at any time in your life is that sound of a mother’s screams; it’s a traumatizing event,” he said.

“When we got in the house, my son asked me all of these questions that’s really, really, really hard to try and tell a 7-year-old. Why is this happening to us? Why is this a constant thing? You see this on the news all the time, but you never would expect it to happen on your block.”

At the corner of 61st and Locust, candles, white carnations, and messages adorn a memorial set up in honor of Wallace. There, huddled under an umbrella, Don and Amy Whitehead stood in silence.

The couple traveled 13 hours from their home in Nashville, Tennessee, to pay their respects and to march with the community and advocate for change in how mental illness is handled.

Don said his son was shot in a confrontation while suffering from a mental health crisis a year and a half ago. He said he’s still looking for answers.

“We heard the news about Walter Wallace and it broke our heart,” said Don Whitehead, who said his son suffered from schizophrenia. “I’m hoping there will be reform across the nation to have more mental health units to come and de-escalate, so we don’t have any more unneeded deaths.”

Amy Whitehead said they drove that distance to support the Wallace family.

“We want to let Walter’s family know they are not alone, even though we won’t meet them, and they don’t know we are here.”

A neighborhood’s history

This is not the first cry out for meaningful police reform.

Wallace’s death is a reminder of a long strained relationship between law enforcement and the Black community in the Cobbs Creek section of West Philadelphia.

Just a few blocks from the scene of Wallace’s shooting is Osage Avenue, where a police standoff 35 years ago with the radical group MOVE ended with 61 homes destroyed and the deaths of six adults and five children.

Police dropped a satchel of explosives onto 6221 Osage Ave. on May 13, 1985, following an armed standoff between police and members of the group.

Nine members had been convicted to life sentences from a standoff several years earlier that left one police officer dead and 16 officers and firefighters injured.

At least 20 MOVE members moved into the Osage Avenue home in 1981, followed by years of complaints from residents over trash and noise from the group leading up to the 1985 bombing.

Jaya Martin was 17 and not far from Osage Avenue when she saw the police helicopter overhead.

“Police were making everybody within five blocks get out of the vicinity at the time. We didn’t really understand what was going on,” Martin said outside her cousin’s Locust Street home Thursday afternoon.ADVERTISING

City officials allowed the fire from the bomb to burn and spread, destroying most of the houses.

“Everybody was frustrated. You can’t imagine, to see people burned and perished, little kids being taken away from their parents,” Martin said.

The bombing gained national infamy as one of the most bungled police standoffs, until the FBI siege of the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas, eight years later.

Even for younger residents, Wallace’s death serves as a constant reminder of the catastrophe on Osage.

“That happened in 1985, I wasn’t born yet, but it still had a big impact on me,” Harris added.

“Knowing that this could happen on any given day, that the same people sworn to protect and serve you can bomb you,” Harris added.

For Marquita Johnson, who moved to Locust Street about eight years ago, Wallace’s death a few houses away has left her young daughters afraid and confused.

“My three daughters are not feeling protected anymore … they feel like the cops hurt instead of help, and that’s sad,” Johnson said.

Johnson said she has always told her three daughters, ages 3, 8 and 9, to call the police in an emergency, and “you scream for police if you don’t have a phone.”

“That’s what I teach my three daughters, and my 8- and 9-year olds just cannot understand why the cops keep killing people, and I can’t explain it them,” said Johnson.

Johnson said she didn’t know Wallace well, but her children and his played together.

“When I got the block, and they told me who it was, I was just shocked… shocked beyond words can explain,” she said.