Foster kids: ‘They are the forgotten children’

Marion Callahan

Published in The Bucks County Courier Times & Intelligencer

Andrew Smith knows how to file a tax return. He knows how to cook a steak, and at 18, he knows the cheapest place to buy one.

But he doesn’t know why he was pulled from his home and separated from his four brothers at age 9. He doesn’t know why the family that fostered him for six years gave up on him when he turned 15. And he still doesn’t know why he bounced from foster homes to group homes without the comfort of knowing at any point just how long each stay would last.

“All four of my younger brothers were adopted (when he lost his foster family) but I was a teen, and no one showed me any interest, whatsoever,” said Smith, who asked that his real name not be used to protect himself and his siblings’ privacy.

At 16, he gave up on the idea of finding a permanent family. Two years later, he’s learning life skills at an independent living facility at Christ’s Home, a Warminster organization that provides residential and other services to infants and children to age 21 as well as seniors.

Smith’s experience isn’t unique, according to those who work with teenagers like him. They say the only thing that’s certain for many teens in county care is uncertainty — about how long they’ll get to stay in a foster home, about where they’ll be sent next, about whether anyone will adopt them.

Children end up in the state’s child welfare system for a wide variety of reasons. A growing number of children and teens are pulled from homes because of parental addiction issues, abuse and neglect, or the family’s inability to care for them.

As a child ages, the chances of finding a foster or adoptive family decline. It’s never been easy for teens, thanks to their often complex needs and the costs of fostering and adopting, said Lynne Kallus-Rainey, executive director of Bucks County Children and Youth. Those factors, along with the unprecedented number of calls coming into county child welfare offices in the region, has the Bucks agency and others trying to find new ways to build connections between teens and area families.

Referrals rising

Since 2015, the number of referrals for placements for children and teens has climbed by 224 percent. Last year, the majority of new placements for children of all ages were related to parental substance abuse, Kallus-Rainey said.

The Bucks agency currently oversees the care of 380 children, including 86 teens. Forty-two of those teens live in foster homes. More than half of the remaining 44 are in group homes awaiting foster placement or live in county-sponsored independent-living apartments.

Montgomery County has responsibility for 320 children under 21. A total of 148 are teens; 69 of them live in foster homes. The rest are in group homes or, depending on their age, small apartments.

Kallus-Rainey and leaders of area child advocacy organizations have formed the Upper Bucks Community Coalition to Support Foster Children and Families, which met recently to brainstorm ways to connect teens with families or to provide community support for foster families throughout the county.

“Child welfare workers can’t do it alone,” said Kallus-Rainey, who hopes community nonprofits, faith-based groups and other volunteers will help the effort.

In Montgomery County, Laurie O’Connor, administrative officer of the Children and Youth agency, said social media outreach and initiatives with nonprofit organizations are raising money to help pay for things such as camp and community sports teams that child welfare agencies can’t provide and that help make fostering or adoption more affordable options for families.

“There is always a need (regardless of age) to know what it’s like to be part of someone’s family,” O’Connor said.

Finding families for kids is what Sandra Schreffler does. She’s a lead recruiter for Diakon Adoption and Foster Care.

“Many (children and teens) have been separated from parents and siblings, had to constantly change schools; it’s no wonder they have anxiety and are fearful of the future,” said Schreffler, whose agency serves Bucks and Montgomery counties, among other areas. “Who can endure so many changes that they didn’t ask for?”

Schreffler said many people fear the challenges of fostering an adolescent — from emotional to financial. Families receive between $24 and $33 a day per foster child, depending on the county, she explained.

“The (money) that they receive may not cover all the things a teen wants or needs, like the cellphones, latest fashions, iPods, music devices or laptops they want,” Schreffler said. “(Emotional) needs are greater because of abuse and neglect they’ve experienced and rejection from other foster homes.”

Adoption prospects

While finding foster families for teens is increasingly challenging, finding adoptive homes is even less likely.

So far this year, only one teen between ages 13 and 19 in the custody of Bucks County Children and Youth has been adopted. In 2016, six teens were adopted. And about five teens a year were adopted from 2012 to 2014, according to county statistics.

Knowing that permanency is a challenge, O’Connor and Rainey said their departments offer services to help teens who remain in the county system learn the skills they’ll need to live on their own before they choose to leave state custody at 18 or age out when they reach 21.

Smith realizes the day is coming when he’ll be on his own.

The 18-year-old, who just graduated from high school, knows he’s not ready for that yet and is taking advantage of the state support services he can receive before he ages out of the system. Right now, he feels safe at his independent living apartment at Christ’s Home, where he’s learning to cook, make financial decisions and balance a checkbook.

He doesn’t have much — most of his possessions would fit in a single suitcase — but he treasures each of them, including a favorite hat, the Pokemon poster on his wall and the stuffed puppy his grandmother gave him. He keeps that by his bedside.

His most treasured possession and his biggest source of comfort is an old framed picture of himself embracing his four smiling younger brothers.

He plans to try to get a job at a local video game store, apply for college and take classes that will lead him to a career as a video game developer. He said he’ll take as much support as he can get for as long as he can can get it, so he doesn’t end up like many youth who age out — homeless and jobless.

‘Forgotten children’

State reports tracking teens who age out of the system without being adopted or living in long-term foster homes are grim, said Lorrie Deck, a director with Pennsylvania’s Department of Human Services’ Office of Children, Youth and Families. A 2015 study, released last year, found nearly 35 percent had been homeless at least once, just under 79 percent didn’t have full-time jobs and nearly 33 percent had been in prison at least once in the previous two years.

John DeGarmo, founder of the Georgia-based Foster Care Institute, said the foster care system in the country is flawed, leaving too many young adults who don’t find homes without the connections and resources to kickstart their lives.

“They are the forgotten children,” said DeGarmo, and the misunderstood ones.

Foster parents need to understand that the first goal of foster care is to reunite children or teens with their parents and to help support that, he said. Foster parents must coordinate visitation with parents and court dates with families and be open to routine home checks and visits from caseworkers, he said.

“The average foster family lasts 18 months and quits,” said DeGarmo, citing national statistics. “It’s an incredibly demanding and challenging job, and sometimes the teen doesn’t want to be in foster care. There is this misconception among families that when a child comes into care, they will be happy, but at the end of the day, they are not mom or dad and it takes some time before that (foster) home is a normal lifestyle for a teen.”

{{tncms-inline content=”

“There is always a need to know what it’s like to be a part of someone’s family.”

Montgomery County Children and Youth Administrative Officer, Laurie O’Conner” id=”031c8c95-5571-425c-aebb-eef6d4a5017d” style-type=”quote” title=”O’Conner Quote” type=”relcontent”}}

Speaking from experience

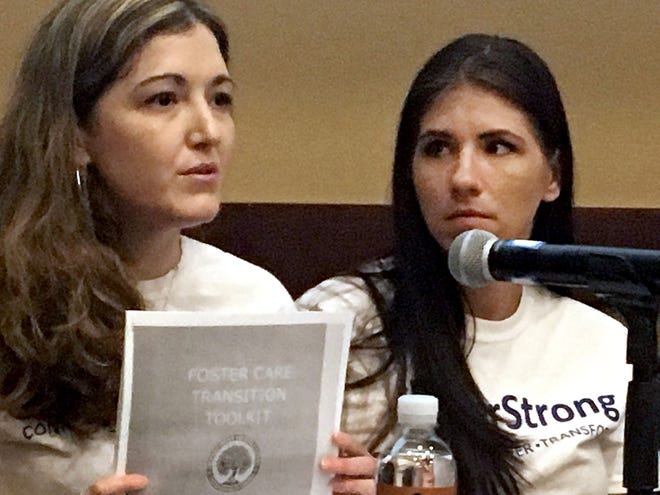

Connie Iannetta, one of 17 directors of Foster Care Alumni of America, agrees.

She speaks from experience. A third-generation foster child — her mother and grandmother also were fostered — Iannetta attended 15 schools and lived in several foster homes before finding a stable home where she stayed until she left the foster system at 18.

Learning to respect a teen’s background and understanding the bond teens share with their birth families is key to good foster care, she said.

“I held my biological family on a high pedestal and it made things difficult,” she said. “Many teens have relationships with their parents, and good or bad, they are still their parents. Some of the most inspiring stories I’ve heard are when foster families mentor the biological family.”

Iannetta said she eventually found a family that felt like home and who recognized her as an individual.

Today, she’s a foster parent to two young children and helps train new foster families. Assisting those families helped her heal, she said, and she hopes others step in and help foster children and families.

“Supporting our most vulnerable youth starts at the community level — people can mentor youth in care, help them find a job or internship, order a family a pizza or donate items for a family getting ready to foster,” she said.

Iannetta’s pleas for involvement are echoed by county, state and national experts who agree that government can’t do it alone.

Kallus-Rainey said the demands placed on foster families, many of whom take in siblings, can be overwhelming.

“We are also working to keep four or five siblings together, make sure the kids are in Cub Scouts, have medical and dental care, get to school activities — all these things,” she said. “It’s a lot for a foster family. One family can’t do all of this, times four, and the public dollar can’t pay for all of it.”

In addition to finding foster and adoptive homes, Kallus-Rainey said Bucks County has a program aimed at locating relatives and family friends of teens in their custody so they have a support network when they transition from county care.

Family reunification has always been Smith’s goal.

He said his parents were unable to care for him and his four brothers when he was younger. Smith hopes to achieve independence, then a career and eventually find a way to reunite with his siblings.

Smith said hope keeps him going.

He hopes he’ll be able to find all four brothers — he knows the location of three. He hopes that his family will be together again. And he hopes that his life will be enriched by the things that brought him comfort as a kid rather than his life being shaped by what’s missing.

“Maybe we’ll find an Old Country Buffet together and have a good meal like we used to,” Smith said. “Then it would be all good.”