By Marion Callahan, USA Today Network, Pa.

The words were not hers, but she delivered them as if they were.

Doylestown Hospital ICU nurse Shumi Mazzacano had two daughters on a FaceTime call, eager to hear what they knew would be the last words from their mother, in the hospital stricken with COVID-19.

Despite the agony of forced separation, one of the pandemic’s cruelest sentences, Mazzacano said the daughters made a choice “out of love” to opt for comfort care instead of a ventilator.

Though minutes away, they couldn’t be at her bedside. No visitors are allowed in.

“It was heartbreaking, and I wanted them to have that moment to say their final goodbyes,” said Mazzacano, who brought her cellphone into the patient’s room and made the call while their mother was still alert.

Through the daughters’ sobs came words of love and gratitude, but through the drone of blowing oxygen, their mother’s response was too hard for them to decipher.

Mazzacano, from the bedside, could make out the labored words.

“She said, ‘I love you.’ ”

“Being part of that intimate moment … I don’t think I’ll ever forget it,” said Mazzacano, her voice cracking. “She was the first patient of mine who passed without a family member there. It’s gut wrenching.”

A look inside

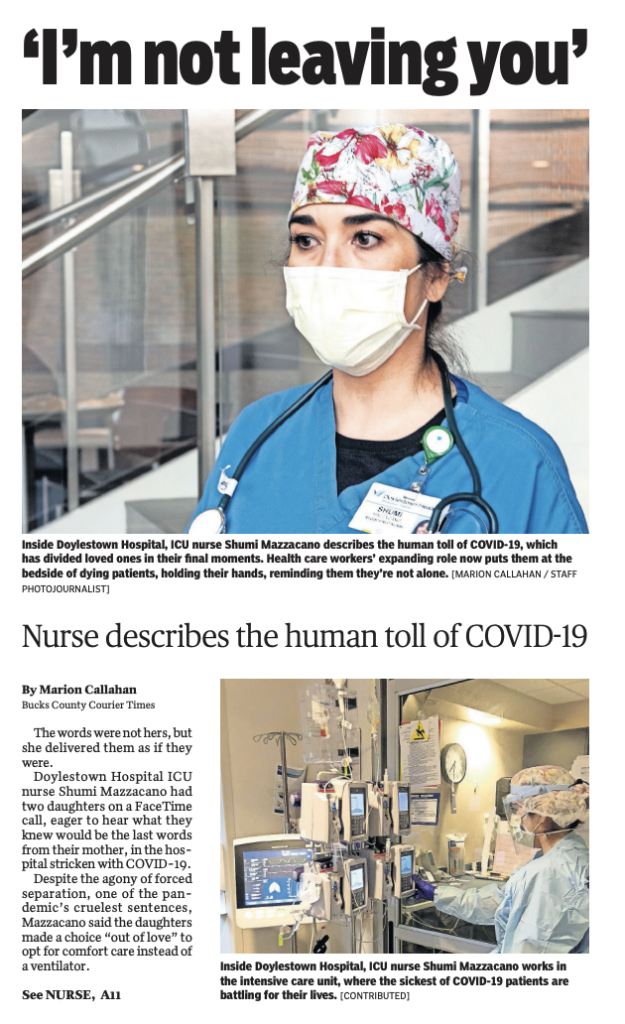

In more than 28 years of delivering care, Mazzacano is navigating a world that’s hard to convey to those living outside hospital walls, where quiet streets and shuttered communities show just a slice of the toll of COVID-19.

Few get a glimpse inside Doylestown Hospital’s ICU unit, where the sickest of patients lay prone, face down, in cluttered rooms with tubing, intravenous drip lines and beeping machines that nurses in face shields and bulky protection equipment must navigate to get to a bedside.

“When your loved one is passing on, you should be there to hold their hand, to allow them to feel the warmth of your skin. The patient doesn’t get that and the loved one doesn’t get it.”

– Shumi Mazzacano, ER nurse

She and her colleagues know their words, their touch, their role as a bridge and messenger between patients and families are all part of their expanding role.

Treating patients who are critically ill isn’t new. But the isolation and unpredictable nature of the virus are.

In the absence of families, nurses sit at their bedsides, comforting them by brushing their hair, holding their hand, rubbing their back or even shaving a gentleman’s face.

Like everyone in the unit, Mazzacano, who works 7:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. three days a week, is picking up extra shifts, as some colleagues who are single parents must limit hours to reduce exposure.

At one time earlier this week, 14 patients were clinging to life inside Doylestown’s intensive care unit, most connected to ventilators and pumps. In total, Doylestown had 40 COVID-19 patients as of Tuesday, and the numbers are rising every week.

Three of those patients were from the same family.

“Two of them are fighting for their lives,” said Mazzacano. A mother and daughter were on maximum oxygen support. The father had been discharged last week, but readmitted Monday night.

“When I saw him rolling in I felt so bad,” she said. “We tried to stop by his wife’s room, so he could get a glimpse of her through the glass door, but there was so much equipment in the hall, we couldn’t navigate the bed around the ventilator.”

One day, Mazzacano connected all of three patients through FaceTime with the couple’s other daughter, who lives out of state.

“She was with her children, speaking to the mother, telling her to fight, not to give up, that they needed her and that she was strong and could get through this,” Mazzacano said “And the husband was pleading, in another room, saying, ’I will take care of you when you get home … please don’t leave me.’ ”

“It’s overwhelming to see how one family can be so devastated, to have two loved ones on maximum life support and another parent positive, now a patient in the ICU again,” said Mazzacano.

The FaceTime exchange is tough for grandchildren, she said, who are not used to seeing loved ones attached to breathing machines and tubes.

Some patients prefer not to have that virtual conversation.

“I had one patient who said he felt so alone, but when I offered to connect him with his family, he didn’t want to; he was struggling so badly to breathe and was afraid it would cause emotional duress for his wife and boys,” she said. “He is still here, fighting for his life.”

Time, hope are fleeting

The virus’ method of attack is stealthy and unpredictable, quickly affecting patients who appear relatively stable.

“They come in talking and breathing on their own, but very quickly decline — like a light switch,” Mazzacano said.

With COVID-19, their lungs are failing, and they can’t meet the body’s demand for oxygen. Coupled with falling oxygen is the fear on patients’ faces as they gasp for breath.

“You try to keep them calm and reassure them, ’You are OK. Breathe slower, in your nose and out your mouth’ … You try to calm them down. There is a lot of panic, because they are afraid this is it. Nobody wants to be on a breathing machine.”

Nurses and respiratory therapists use meditative techniques to calm patients and ease anxieties.

“I’ll ask them to close their eyes, and I’ll breathe with them, so they can follow my breath and I reassure them. ’We got you … We are right here.’”

With some patients, she must limit contact, for her own safety and the safety of her family, and speak through a glass window.

“One gentleman wanted me to stay in his room,” said Mazzacano. “He said he was scared and needed human contact. I stayed for as long as I could.”

She then parted the curtains in his room, showed him where she could be seen through the glass and said, “I will not leave you.”

The patients, she said, are incredibly understanding and brave.

One patient in his early 40s, who weighed too much to be put in a prone position, knew what he was facing and that his size limited his therapy. Still, she can’t shake the expression of acceptance when he was told he would require a ventilator to breathe. “He just closed his eyes and nodded his head.”

She offered to call family, “He shook his head, no.”

“Even though he understood … that realization you see when a patient knows this may be it … that part is so difficult.”

She said nurses cling to hope and cheer on patients who are showing progress, as oxygen levels rise and patients get more meals down. “But all that hard work … it can change so quickly.

“They’ll make strides in oxygen, then they’re back down to 86% with maximum oxygen support,” said Mazzacano, adding those numbers are deadly and require intensive respiratory intervention.

“They are fighting for every breath and sometimes the slightest stimulation, a small shift of their body, can put them ’over the edge’ and they’ll be on the ventilator. The mortality rate goes up tremendously once put on a breathing machine.”

Mazzacano and her colleagues want to be there in the end, and they are alert to the body’s signals, the dropping of heart rate and oxygen levels and a bluish tint to the skin.

“I don’t like people to die alone; we hold their hands, tell them their family loves them. We may adjust morphine drips for comfort. And we let them know that it’s OK to go.”

Community and camaraderie

With each patient Mazzacano loses, the emotional scars deepen. But on the unit floor, she keeps a brave face. “We have to be strong for the patients and the family members,” she said.

She draws strength from the outpouring of community support, the signs, the cards and the donated meals. One kind gesture brought her to tears as she walked through the hospital’s entrance one day when she happened to look down.

“I saw a brightly colored fluorescent yellow rock with the hashtag, #nursesrock,” she said. “Things like that lift you and allow you to do your job better.”

Inside, Mazzacano doesn’t have to search far for support, because as in war time, there is camaraderie among peers.

“We thank each other; we help each other. If we see someone stressing out, we step in. We tell them, ‘Go, we got this.’ ”

Staff on the unit know the signs of fatigue.

“We’ll see someone shaking and we know they didn’t have lunch; we know who’s eating and who’s not because we cover each other for lunches.”

Every week brings new challenges.

“In the beginning it was really stressful learning how to limit exposure, in what order to take PPE off,” she said. “It’s the little things we never had to think about. Then it was, how do we find supplies?”

Operating room nurses from other departments watch each other don and doff protective gear, making sure every step and precaution is followed. The laborious process can take up to several minutes.

“Everything is slow and purposeful with protection; you can’t rush to do anything — even though you may hear machines beeping or oxygen levels dropping on a patient.”

Uncertainty looms

Mazzacano worries about who is going to take their place when the hospital reopens soon for elective surgeries and the observers return to operating rooms.

With the present surge of patients from nursing homes, many families are moving away from aggressive treatment, following “Do Not Resuscitate” orders. She expects more deaths to come as a result of that.

Now, as protective procedures are ingrained in work routines, the source of stress has shifted to emotional challenges of patient care and even self care.

Traumas of the day typically settle in at night.

At home, she sleeps in the basement and is socially distanced from her husband, her 19-year-old son and her 22-year-old daughter. “Even life at home is disrupted,” said Mazzacano, who misses her bedtime rituals.

Her mind inevitably wanders to her patients, most recently a man who is in his 50s. “That could be my husband. That could be me.”

When she’s out in the community, scenes unfolding in the grocery store or at the gas pump worry her.

“It upsets me when I see people walking around with N95 masks in supermarkets and wearing gloves and touching everything and then touching their faces, not sanitizing in between,” said Mazzacano.

One woman who she saw pumping gas “came out in her N95 mask and gloves; pumped gas, touched the steering wheel, reached into her purse, put the card away in her wallet, and then touched the screen of her phone with the dirty gloves.”

Mazzacano knows there are some people who dismiss the threat of the virus.

“For people to really grasp it, I would love for them to experience a day in here.”

Mazzacano likens it to chaotic “footage you see of hospitals in other countries … the way people are running around, as alarms from ventilators are setting off, monitors and IV pumps beeping and physicians and nurses literally yelling because of the noise and how hard it is to hear because our voices are muffled because we have masks and face shields on.”

As of now, she sees little assurance that her landscape inside the walls of the intensive care unit will change. “It seems never ending … You don’t know if it’s going to end.”

But Mazzacano, like her patients, is reminded she is not alone.

“These emotions and experiences are echoed throughout my unit,” she said. “We have become the link to our patients and their families to keep hope alive, to keep them fighting and reminding them they are loved so deeply.

“I am grateful for the continued love and support from my family, coworkers, friends, and community. It is a reminder that we are there not just for those inflicted with COVID, but also to keep all those around us safe and healthy.“

Still, the idea of easing social distancing restrictions, along with talk of people eager to return to their gyms, frightens her.

“It scares me because there is no cure, no vaccine and we are running out of PPE. What scares me is that this will go on and we will run out of PPE … We still have to care for these patients.”

Mazzacano knows everyone’s perspective of the virus is different, but emphasized the stark contrast between the view inside hospitals and the view outside.

“Everything is so pristine and peaceful outside the hospital, and even inside parts of the hospital, it’s quiet … People aren’t visiting, elective surgeries are canceled. No hospital looks busy right now.

“But inside these walls, it’s mayhem.”